Title: Rehearsed Futures: Supplementary school performances in and beyond the Museum of London

My research examines how remote landscapes continue to be revisited by children of migrant backgrounds, and how their cultural and place-based identities are created through sites of collaboration between UK based supplementary schools and the Museum of London.

The focus of my research are supplementary schools set up by migrant communities, who have collaborated with the museum between 2017-2020. In supplementary schools a mixed curriculum with an emphasis on mother-tongue language lessons, storytelling and performances becomes a tangible and personal way for children to connect with their parents’ countries of origin. At the museum, children perform school plays about their cultures, evoking their parents’ home-countries through soundscapes, movement, dress and narration.

The case-studies of London-based Albanian, Tamil, Lithuanian and Brazilian supplementary schools explore how children remember their parents’ places of origin post migration, how these places are reconstructed through language and mythology, how children’s performances revise geographies, and finally, how performing becomes a route through which new and old places are revisited.

Following Alice Elliot’s research on waiting as a precondition of transnational migration towards Europe (Elliot 2016), I suggest that in the context of supplementary school rehearsals children from migrant backgrounds practice corporeal anticipation (Sennett, 2008:175), synchronising their steps and speech and coordinating their moves in response to their present location and changing settings. Drawing on how “the body itself serves as a field of localization” (Merleau-Ponty), my observational sketches of school rehearsals point to how children as actors generate space and continually adjust their positions (Johnstone 2007) as their reinterpret traditional roles and improvise new cultural forms.

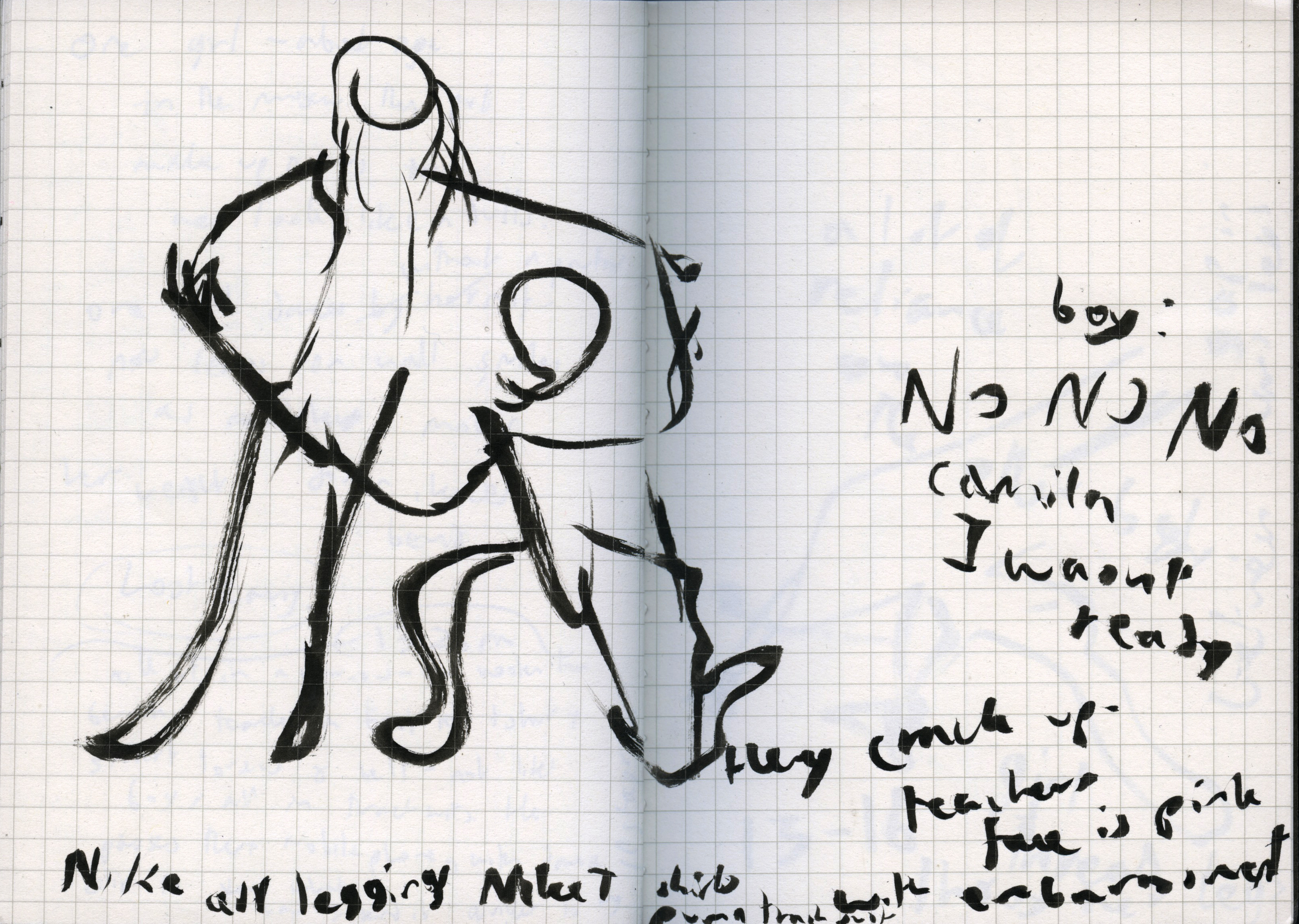

1. ‘no no no Camila, I wasn’t ready’ – children from EC Lighthouse Supplementary School rehearsing Latin Ballroom dance. (Sketchbook)

2. Children from EC Lighthouse performing at the Museum of London.

Touring performances enable a group of older children to travel internationally, revisit their home and neighboring countries, and venture out as far as Disneyworld by performing in international competitions:

For children attending EC Lighthouse, a Lithuanian supplementary school, touring performances enable one group to revisit their home and neighboring countries, and venture out as far as Disneyworld. Children have travelled near and far, performing in international competitions.

Lessons at the Lithuanian supplementary school comprise of ballroom dancing, Lithuanian as mother-tongue language, Russian and Spanish, craft and drama. When I visit, I find a group of 9 students aged 14-16 in a Latin and Ballroom dance rehearsal, practicing new moves. “Pray for me,” jokes a young girl, as she prepares for her dance partner to run across the room towards her, jump on her, then catch her and support her weight a millisecond before they hit the ground. This is the first time they are being taught this move. They fail and both fall on the soft mattresses. We all laugh as they practice and fail a second and third time. There is clearly a lot of trust involved. The students know each other well, they have grown up together and have been attending this school since they were young children. They now tour internationally, perform frequently at the Museum of London during festivals, between a busy line-up of international venues.

Waiting in their starting positions, one girl stands with her back towards her partner who kneels behind her, holding each other’s wrists. When music comes on and she jerks forward, yanking his arm. “I wasn’t ready,” he yelps. When performing in public they seem to glide across the stage, the precision of choreography concealing the work involved. Their Saturday school rehearsals reveal how they are still learning to coordinate their steps and anticipate their partners’ move, their reliance on other bodies, the trust and risk involved.

I ask the students where they prefer to perform, expecting them to name a country or city, but their perceptions of place are more detailed, and they discuss different types of stages. A raised stage is not essential, but preferable. They describe dancing in a Town Square in Latvia. “it was scary’, one girl recalls, ‘as people kept coming towards us’. There was no stage at all. “Dancing on the stony ground, with gravel, gross, dust made your shoes grey,” one girl explains. ”But some raised stages are terrible”, another girl remarks, and recalls a raised stage with gaps between planks, your shoe gets stuck between the planks, you can rip your tights and get splinters”. This was during their visit to Austria, where they performed in three different locations.

3. Street dance class, TALA (Tamil Saturday School) London.

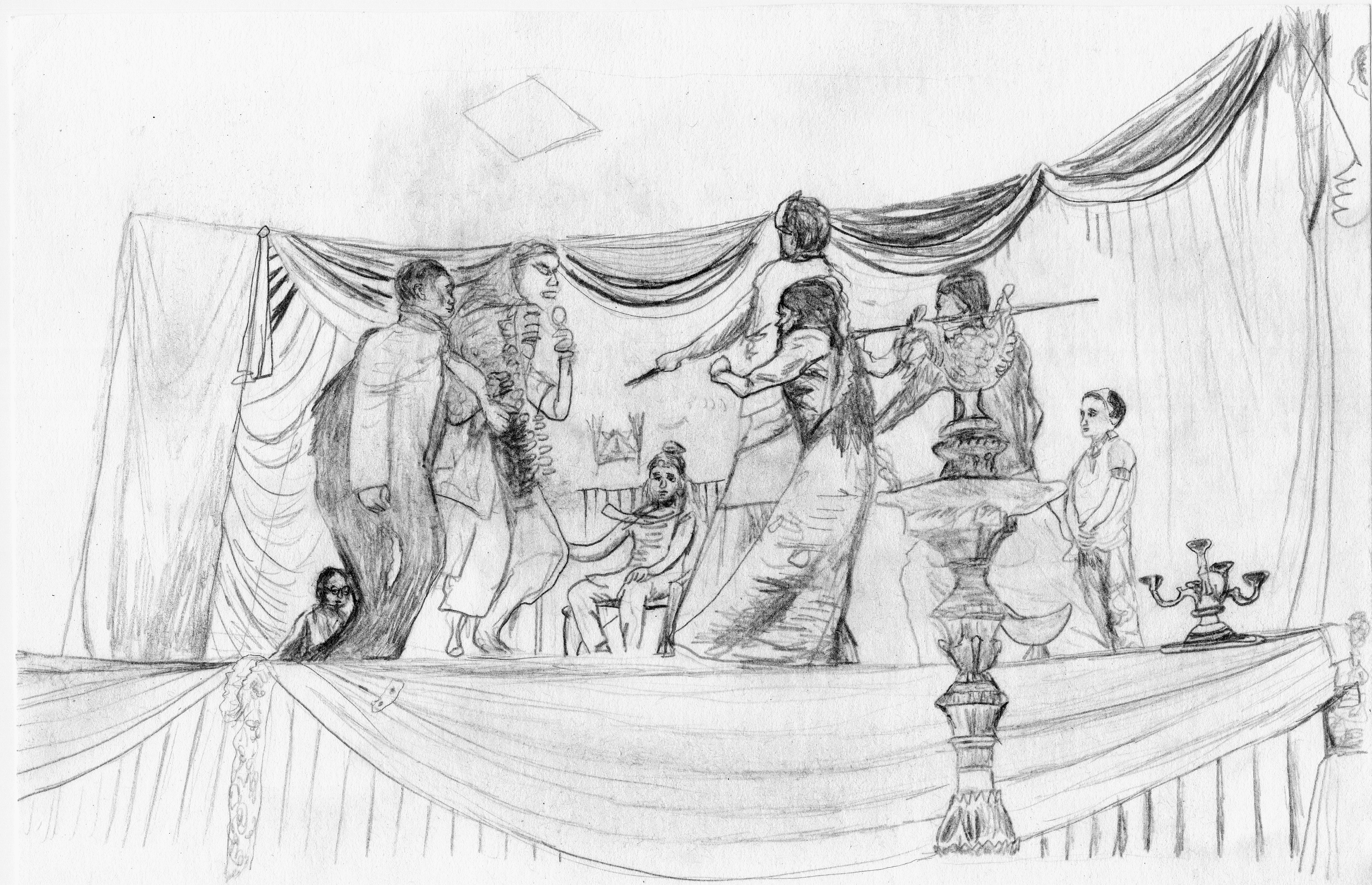

4. Murugan defending villagers from their attackers on a London temple stage, performed by TALA students.

When I visit a TALA, a Tamil supplementary school in East London, children rehearse a sacred play about the creation of Murugan. The school teaches Tamil as mother-tongue, street-dance and drama. Their drama repertoire is wide-ranging, including sacred plays, pedagogic performance and political activism, as well as Tamil street dance. Performances are adapted to different contexts and settings, including museums, temples, the Houses of Parliament and a West End auditorium. The versatility of their staged performances enables children to access the city through its cultural venues, creating new urban identities and experiences. Through their plays children learn about citizenship, rights and campaigning, practicing their oratory skills and how to communicate cross-culturally and to different audience.

5. School play of Rozafa castle, Shpresa school. Museum of London.

6. Rebuilding the castle, Shpresa school. Museum of London.

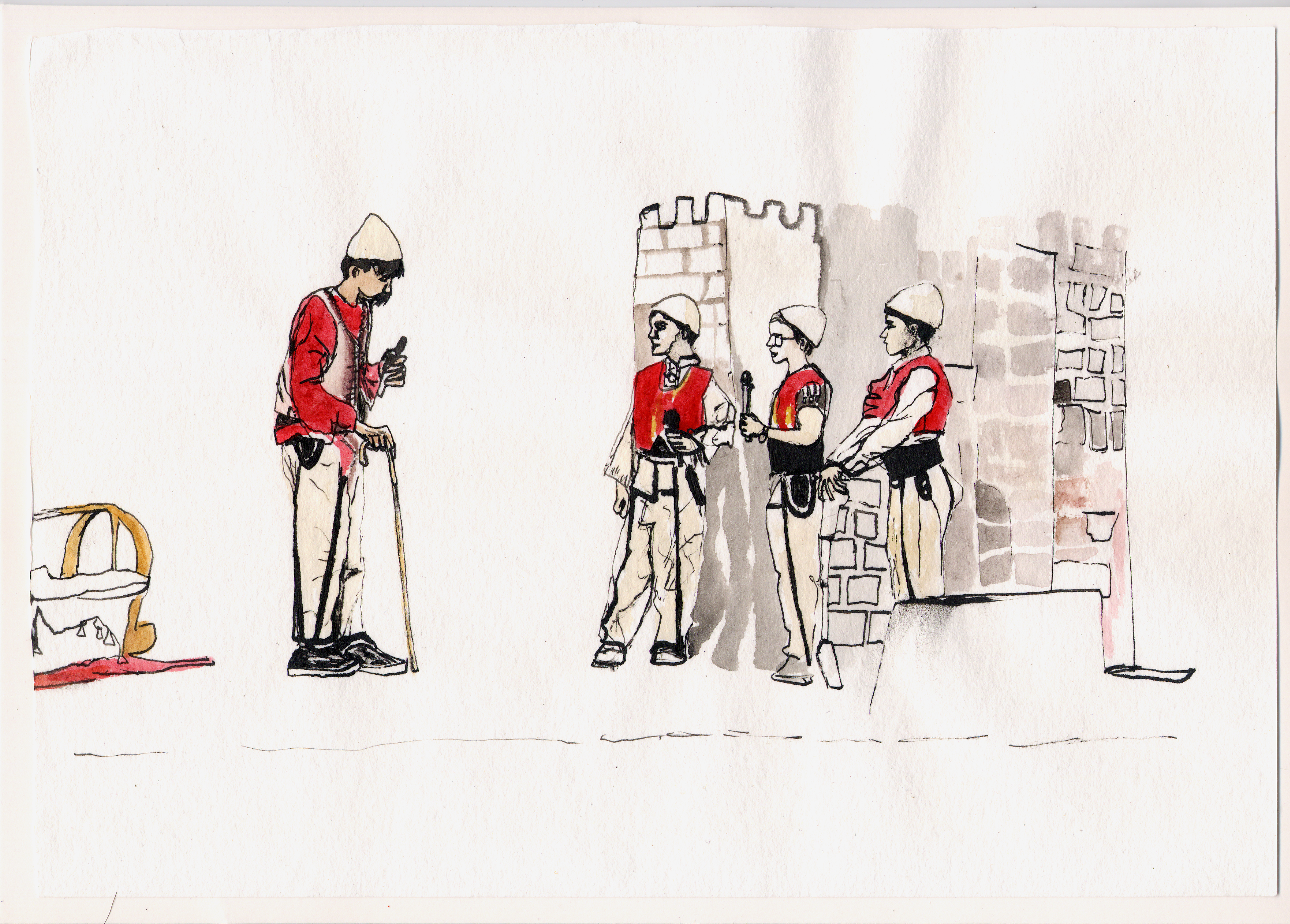

7. Boys returning to work. Rozafa castle school play. Shpresa school at the Museum of London 2020.

8. Old man reveals secret. Rozafa castle school play. Shpresa Albanian supplementary school at the Museum of London 2020.

9. Girl caught between the castle and cradle. Rozafa castle school play. Shpresa Albanian supplementary school at the Museum of London 2020.

10. Handing the baby, end scene. Rozafa castle school play. Shpresa Albanian supplementary school at the Museum of London.

In an Albanian supplementary school, language is a site of heritage which extends to mythology and folklore. The school is part of Shpresa programme (meaning hope), an organization that provides services and support for Albanian speaking migrants and refugees, promoting integration with dignity and cultural pride, developing a sense of Albanian-British identity in London, and building communities of trust.

The school teaches children Albanian as mother-tongue, whilst their parents can take English language lessons in an adjacent room. As well as language skills, children also learn Albanian folk dancing, drama, geography, history and art.

During my fieldwork, children from Shpresa performed the legend of Rozafës castle twice at the Museum of London. The story is about a castle that keeps collapsing and has to be rebuilt. At the Museum of London, the children reconstruct this famous landmark on stage. Boys crouch by the foot of the cardboard castle and set to work, pretending to dig and build with hammers and shovels. They are wearing traditional Albanian dress- Qeleshe (red waistcoats), Tirq (white trousers with black vertical stripes) and white skull cups. Gathered round a wooden rocking cot, girls sing ninna-nanna (traditional lullabies) evoking Albania through soundscape.

In the story the heroine is asked to enter the wall of the castle in order for it to stand. She agrees on the condition that her body is divided, half of her remaining in the external world so she can look after her baby, and her other half resides in the castle wall. The story speaks to the embodied experience of migration, where the self is often doubled or halved, living in two places, stretched across temporalities, geographies, obligations and borders. This folk-story, loaded in meaning, at once evokes a sense of Albania, describing a real place, and the experience of migration that continues to form part of Albanian memory.

The closing scene is hard for the children to perform, no one is sure where to stand, since this is a metaphysical proposition. The girl stands on stage between the folds of the cardboard castle so half of her is inside its walls. The boy approached her with their baby doll to complete the tableaux. Their teacher rearranges their positions, and the stage becomes a place where heritage is improvised and reworked.

In the Albanian, Tamil and other supplementary school performances, children become orators of their cultures and inherit the role of leading their communities, establishing new relationships between their schools and the museum.

‘Past, Present, Future’

In Clube dos Brasileirinhos, a Brazilian Saturday school based in London, children are taught Portuguese as a heritage language as well as drama, storytelling and capoeira. In a drawing and film workshop I organized for the drama group, I asked children to draw their memories of Brazil, their present Saturday school, and how they imagine the future. Using a projector the children improvised scenarios and acted inside their drawings. The film reveals the layered environments in which children are brought up, where their knowledge and memories of Brazil are mixed with the textures of an English classroom. Through their drawings, conversations and play I learned of the children’s impressions of Brazil, how it features in their individual biographies, where they situate their London Saturday school in relation to Brazil, and their ambitions and hopes for the future. The workshop took place in their London classroom over two consecutive Saturdays in March, 2020.